# init repo notebook

!git clone https://github.com/rramosp/ppdl.git > /dev/null 2> /dev/null

!mv -n ppdl/content/init.py ppdl/content/local . 2> /dev/null

!pip install -r ppdl/content/requirements.txt > /dev/null

Probability and likelihood#

import numpy as np

from scipy import stats

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import pandas as pd

from rlxutils import subplots

import itertools

%matplotlib inline

We have data representing draws of a biased coin.

but we don’t know the probability of the biased coin.

This is a Bernoulli distribution with unknown parameter \(p\).

The probability assigned to \(x\), depends on a choice of \(p\)

Probability#

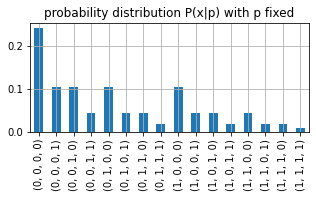

If we set \(p\) fixed and consider different datasets we have a discrete probability distribution, that assigns a probability to each dataset. And, in this very simple setting, we have 16 possible datasets.

In all practical settings having an exhaustive list of all datasets is simply impossible. Think, for instance, of all possible datasets of 1000 customers described by age, profession, income, credit history,…. This would mean all combinations of all possible values for each feature.

all_datasets = np.r_[list(itertools.product(*[[0,1]]*4))]

all_datasets

array([[0, 0, 0, 0],

[0, 0, 0, 1],

[0, 0, 1, 0],

[0, 0, 1, 1],

[0, 1, 0, 0],

[0, 1, 0, 1],

[0, 1, 1, 0],

[0, 1, 1, 1],

[1, 0, 0, 0],

[1, 0, 0, 1],

[1, 0, 1, 0],

[1, 0, 1, 1],

[1, 1, 0, 0],

[1, 1, 0, 1],

[1, 1, 1, 0],

[1, 1, 1, 1]])

the conditional probability function

P_x_given_p = lambda x,p: np.prod(stats.bernoulli(p).pmf(x))

we fix p, so we have a function of x

fixed_p=.3

P_x_fixed_p = lambda x: P_x_given_p(x, fixed_p)

and we DO have a discrete probability distribution for this fixed p.

The expression \(P(x|p)\) with a fixed \(p\) and varying \(x\) is a discrete probability distribution.

probs = np.r_[[P_x_fixed_p(dataset) for dataset in all_datasets]]

print ("all probabilities", probs)

print ("\ncheck sum of probabilities", np.sum(probs))

all probabilities [0.2401 0.1029 0.1029 0.0441 0.1029 0.0441 0.0441 0.0189 0.1029 0.0441

0.0441 0.0189 0.0441 0.0189 0.0189 0.0081]

check sum of probabilities 0.9999999999999998

pd.Series(probs, index=[tuple(i) for i in all_datasets]).plot(figsize=(5,2), kind='bar')

plt.grid();plt.title("probability distribution P(x|p) with p fixed")

Text(0.5, 1.0, 'probability distribution P(x|p) with p fixed')

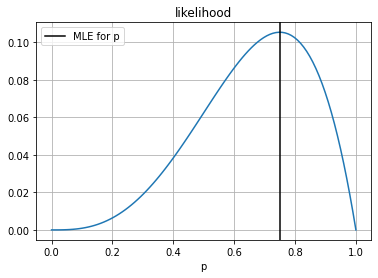

Likelihood#

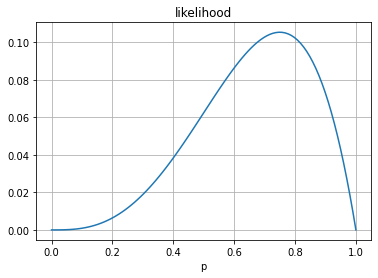

If we set \(x\) fixed and consider different values of \(p\) we have a likelihood function. This IS NOT a probability function

We fix \(x\), so we have a function of \(p\)

fixed_x = np.r_[1,0,1,1]

likelihood = lambda p: P_x_given_p(fixed_x, p)

this is a continuous function, and it is not a probability distribution since it does not integrate to 1.

in this case the integration is between 0 and 1 since, by definition, \(p \in [0,1]\)

pr = np.linspace(.0,1., 100)

plt.plot(pr, [likelihood(pi) for pi in pr])

plt.title("likelihood"); plt.grid();

plt.xlabel("p");

# the integral

from scipy.integrate import quad

quad(likelihood, 0,1)[0]

0.05

Maximum likelihood estimation#

but we can ask, what is the value of \(p\) that that assigns more probability to the data that we have seen?

from scipy.optimize import minimize

# negative function for maximization

# constrained to possible values

r = minimize(lambda p: -likelihood(p), np.random.random(),

constraints = ({'type':'ineq', 'fun': lambda p: p},

{'type':'ineq', 'fun': lambda p: 1-p} )

)

r

fun: -0.10546865449586039

jac: array([-0.00065521])

message: 'Optimization terminated successfully'

nfev: 13

nit: 6

njev: 6

status: 0

success: True

x: array([0.74970856])

pr = np.linspace(.0,1., 100)

plt.plot(pr, [likelihood(pi) for pi in pr])

plt.title("likelihood"); plt.grid();

plt.xlabel("p");

plt.axvline(r.x[0], color="black", label="MLE for p")

plt.legend()

<matplotlib.legend.Legend at 0x7fe756162400>

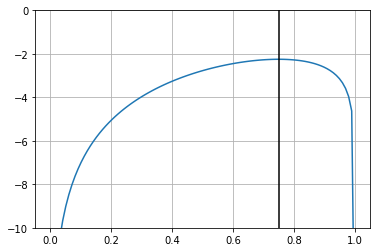

and one usually maximizes the \(\log\) likelihood since it is monotonic, nicely turns multiplications into summations and has much less numerical issues.

To maximize the likelihood, we maximize the log likelihood.

# original conditional distribution function

P_x_given_p = lambda x,p: np.prod(stats.bernoulli(p).pmf(x))

# log likelihood function

log_likelihood = lambda p: np.sum(np.log(stats.bernoulli(p).pmf(fixed_x)+1e-7))

np.exp(log_likelihood(.2)), likelihood(.2)

(0.006400010400006, 0.006400000000000002)

r = minimize(lambda p: -log_likelihood(p), np.random.random(),

constraints = ({'type':'ineq', 'fun': lambda x: x},

{'type':'ineq', 'fun': lambda x: 1-x} )

)

r

fun: 2.2493397926615546

jac: array([-0.00077778])

message: 'Optimization terminated successfully'

nfev: 13

nit: 6

njev: 6

status: 0

success: True

x: array([0.74996358])

plt.plot(pr, [log_likelihood(pi) for pi in pr])

plt.ylim(-10,0); plt.grid();

plt.axvline(r.x[0], color="black", label="MLE for p")

<matplotlib.lines.Line2D at 0x7fe7560921c0>

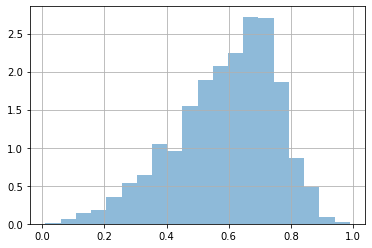

Likelihood on continuous distributions#

let’s consider the data from the UCI ML repository, Abalone dataset

we will focus only on the marginal distribution of the variable length, and we will scale it so that it has values between 0 and 1

dataset = pd.read_csv("local/data/abalone.data.gz",

names=["sex", "length", "diameter", "height", "whole weight", "shucked weight",

"viscera weigth", "shell weight", "rings"])

from sklearn.preprocessing import MinMaxScaler

x = dataset['diameter'].values

x = MinMaxScaler(feature_range=(0.01,.99)).fit_transform(x.reshape(-1,1)).reshape(-1)

#x = x[np.random.permutation(len(x))[:1000]]

plt.hist(x, bins=20, density=True, alpha=.5);

plt.grid();

We are told that MAYBE we can model this data with a \(\mathcal{B}\) (beta) distribution.

Seeing the shape of our histogram and the shapes produced by a \(\mathcal{B}\) distribution this seems a reasonable assumption.

The beta distribution is governed by two parameters, \(a\) and \(b\).

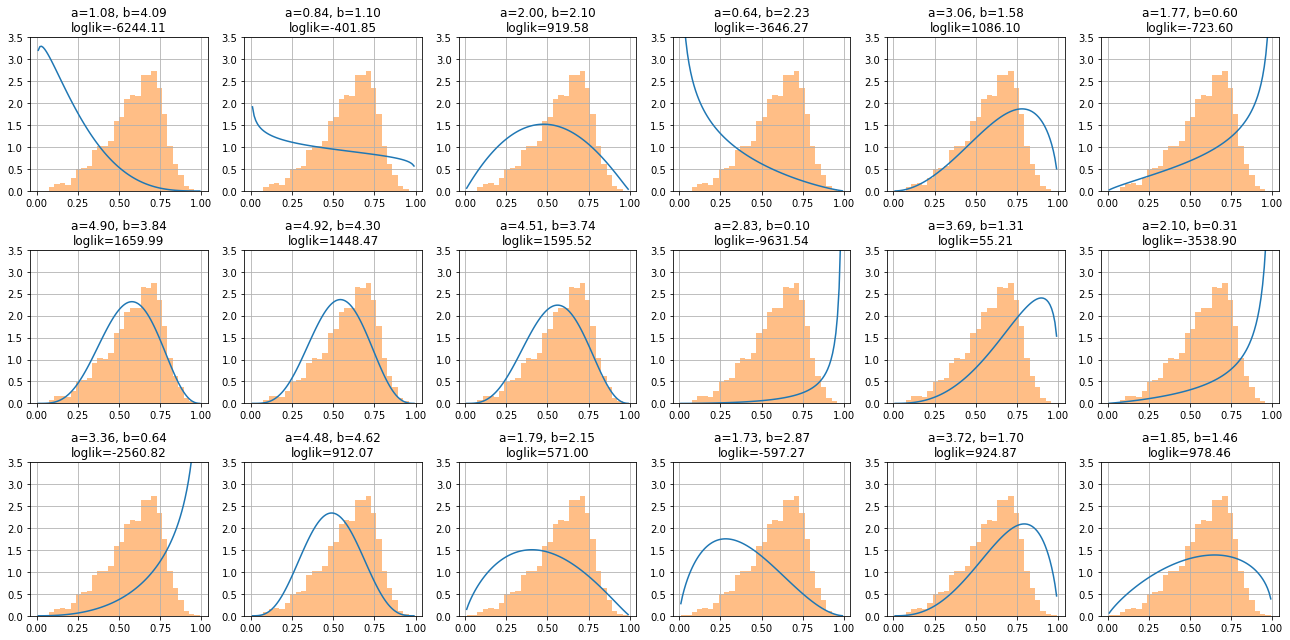

We show now several \(\mathcal{B}\), and the log likelihood is a function of two parameters

loglik = lambda a,b: np.sum(np.log(stats.beta(a,b).pdf(x)+1e-7))

xr = np.linspace(0.01,.99,100)

plist = list(itertools.product(ar,br))

for ax,_ in subplots(18, n_cols=6):

a,b = (np.random.random(2)+.01)*5

beta = stats.beta(a=a, b=b)

plt.plot(xr, beta.pdf(xr))

plt.title(f"a={a:.2f}, b={b:.2f}\nloglik={loglik(a,b):.2f}")

plt.hist(x, bins=30, alpha=.5, density=True)

plt.ylim(0,3.5)

plt.grid();

plt.tight_layout()

Likelihood intuition#

observe that parameters \(a\) and \(b\) producing functions more different to the histogram have must higher log likelihood.

Maximum Likelihood’s intuition is let’s assign what I see the highest possible probability:

We now find the MLE by brute force.

from progressbar import progressbar as pbar

ar = np.linspace(.5,10,200)

br = np.linspace(.5,10,200)

dr = (ar[1]-ar[0])*(br[1]-br[0])

r = np.r_[[loglik(a,b) for a,b in pbar(itertools.product(ar, br), max_value=len(ar)*len(br))]]

r=r.reshape(len(ar), len(br))

100% (40000 of 40000) |##################| Elapsed Time: 0:00:32 Time: 0:00:32

ai, bi = np.unravel_index(r.argmax(), r.shape)

ar[ai], br[bi]

(4.796482412060302, 3.3643216080402008)

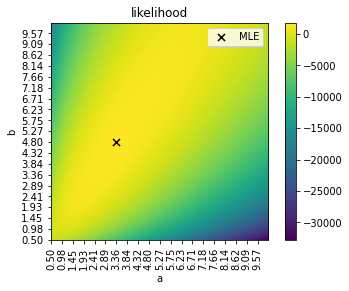

this is the search space and the values for \(a\) and \(b\) yielding the best likelihood.

plt.imshow(r, origin="lower")

plt.colorbar();

plt.xticks(range(len(ar))[::10], [f"{i:.2f}" for i in ar[::10]], rotation="vertical");

plt.yticks(range(len(br))[::10], [f"{i:.2f}" for i in br[::10]]);

plt.xlabel("a")

plt.ylabel("b")

plt.title("likelihood")

plt.scatter(bi, ai, marker="x", color="black", s=50, label="MLE")

plt.legend();

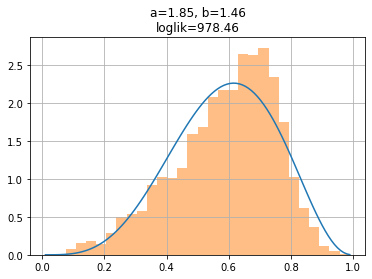

observe how this makes intuitive sense, fitting reasonably well the distribution.

beta = stats.beta(a=ar[ai], b=br[bi])

plt.plot(xr, beta.pdf(xr))

plt.title(f"a={a:.2f}, b={b:.2f}\nloglik={loglik(a,b):.2f}")

plt.hist(x, bins=30, alpha=.5, density=True)

plt.grid();

Of course MLE, as any optimization, becomes much harder when we have a multivariate setting